|

Rush - A Ghost Along The Buffalo

By Evelyn Wilson Parker

There is a place in the Arkansas Ozarks where men once dreamed of silver mines, toiled beside a gem of a river called the Buffalo to unearth countless tons of common zinc--and ironiccally won a gold medal for their efforts.

This place is Rush, nestled between Rush and Clabber Creeks on the Buffalo River in southern Marion County, Ark., five miles north of Buffalo Point off Ark. Hwy. 14.

Few canoeists, who glide by only feet from what was once the largest city in northwest Arkansas, notice beneath the shoreline tangles of vines and brush the evidences of man's intrustion here. Rush's heydey has passed; its future decided. Rush is and will remain a ghost town. The mines with their fancy names--Morning Star, Lucky Dutchman, Dixie Girl, Monte Cristo--are off-limits. The National Park Service protects Rush's remains with care and respect, but most of its still-standing structures are but moldering skeletons.

Few canoeists, who glide by only feet from what was once the largest city in northwest Arkansas, notice beneath the shoreline tangles of vines and brush the evidences of man's intrustion here. Rush's heydey has passed; its future decided. Rush is and will remain a ghost town. The mines with their fancy names--Morning Star, Lucky Dutchman, Dixie Girl, Monte Cristo--are off-limits. The National Park Service protects Rush's remains with care and respect, but most of its still-standing structures are but moldering skeletons.

Persisten Indian legends of lost silver mines drew prospectors John Wolfer, Bob Setzer and J.H. McCabe to Rush in 1880, where they spent months tunnelling for the coveted ore. THe initial assay report from their efforts erroneously listed $8-a-ton worth of silver in their ore.

Excitedly, the men had a small rock smelter built, firing up its first run in 1886. That run produced a spectacular display of zinc oxide fumes around the stack of the smelter, but the expected silver did not collect in the sand molds at the bottom. The discouraged propsectors offered to trade their holdings--with the smelter thrown in--for $2.50 worth of cove oysters. Their offer was rejected.

It soon became apparent there were many large deposits of carbonate of zinc of a very high grade in south Marion County. However, operations did not really begin until the Morning Star Mine was opened in 1884.

As the industry got started, evidence of associated health hazards soon became apparent. An early casualty connected to the mining efforts was noted in The Mountain Echo edition of Dec. 16, 1887: "Mr. Sebran L. Wiggins died at his residence on last Saturday... He was at work at the zinc mines when he was first taken sick and was brought home. His sickness, it is supposed, was caused by exposure while at the mines. Dr. Wilson, who attended him, pronounced his disease typhoid pneumonia... He leaves a widow and several children to mourn his death."

|

| The Morning Star Store and mine office at Rush, Ark., about 1915. |

That episode did not dampen the enthusiasm of those trying to develop the mining industry, though, and in the Dec. 23, 1887, edition of The Mountain Echo, appeared a notice about a stockholder of the Rush Mining Company stating the outlook for mining was "very bright" with "capitalists and miners coming in almost daily." However, he did confess, "The only trouble now is transportation facilities. This problem is yet to be solved."

Transporation, was, indeed, a problem that would take much ingenuity to overcome. Because of the rough nature of the country and difficulty of access, little production was accomplished until 1889, when a group of men formed a company, opened up the ore lodes, and cut a road to connect with the highway to Yellville.

By 1890, the town had grown sufficiently to be officially named Rush and have its own post office.

The Morning Star continued as the most famous of the Rush mines. In fact, the largest piece of free carbonate ore that was ever mined was extracted from there in 1893. This single mass of pure zinc carbonate weighed 12,750 pounds, and the mine owners were quick-thinking enough to realize its potential in terms of publicity. Named Jumbo by the miners, it staggers the imagination to picture this huge chucnk of ore being dragged on teh front wheels of a large log wagon drawn by 16 oxen. The wagon had logs fastened to the front wheels and the chunk of carbonate of zinc was chained to the logs. It was hauled from the mine to the Buffalo River, where it was floated on a large raft down to the White River. There, it was transferred to a steamboat, taken to Batesville, Ark., removed to a railroad car, and transported to the site of the 1893 Worlds Fair at Chicago. It was exhibited, won a gold medal and first award premium, and created enormous public interest in the Arkansas zinc mines. Zinc ore from the Morning Star Mine also won the first award at the St. Louis World Fair in 1904. Both ores were put on display, with Jumbo housed at the Field Museum, in Chicago, and the later at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.

Methods of travel for people moving in and out of Rush were improving by 1899. In September, 1899, an announcement by the Kansas City, Fort Scott & Memphis R.R. stated: "On Tuesday, Oct. 10, 1899, the Inter-State Express & Stage Line will begin the operation of a daily modern equipped stage line between West Plains, Mo., and Yelllville, Ark. Stage will leave West Plains at 6 a.m., arrive at Yellville at 8:30 p.m., making this the quickest and only comfortable route to the Great Zinc and Lead Mine District of Northern Arkansas..."

|

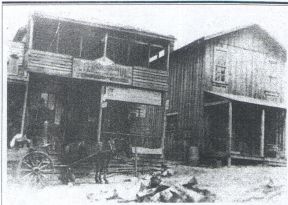

| Rush at the turn of the century. |

Through the next decade the mines flourished, and 17 of them were in operation in the Rush Creek District. Tools of the trade needed for this occupation were obvious in this ad placed in The Mountain Echo on Sept. 30, 1902: "Wanted: 100 teams to haul ore from the Morning Star Mine to Buffalo City Landing. Apply to G.W. Chase, at Rush, P.O., Marion Co., Ark."

An assortment of mine names appeared on laborer's paychecks during the next few years. The Red Cloud, Lonnie Boy, Edith Mill, Yellow Rose, Climax, Mary-Hatta-Anna, Mattie May, Morning Star, McIntosh, White Eagle, Lucky Dutchman, Dixie Girl, Old Mirror, Bonanza, Philadelphia, Monte Carlo, Silver Hollow, Leader, Beulah, The Creek Dig, The Hill Dig, Yellow Jacket, Leader Tunnel, Last Chance, Ben Carney, Capps, Monte Cristo, and Leader Hollow were names that produced excitement and hope for prosperity. While most were not singularly important at the time, they combined to make financial security for the business of Rush.

The miners generally used picks and shovels to mine most of the ore, bu sometimes dynamite would be exploded to break the chunks into smaller pieces. This was done so that they could load them into cars to be hauled out of the mine and dumped into ore bins.

(Apparently the ore was sometimes hand carried from the mine and processing plant. Fred Dirst was a native who began his own mining career with the boyhood job of stoking the boiler at the Lonnie Boy Mine. He noted in the "history of Marion County," by Early Berry, that "Ore was carried from the mine and processing plant by a boy, paid 75 cents a day, who carried several loads of 75 to 80 pounds each.")

Hauled in mass by wagon over the rough, steep roads, two or three teams of horses or mules were often needed to pull a load of ore to the railroad stations at Summit or Buffalo City. There it was loaded onto freight cars of the Missouri Pacific Railroad, was taken to the smelter in Joplin, Mo., was smelted, then run into bars of what was called spelter.

The ore brought $14 per ton at the smelter in 1914. The cost to haul a ton to the railroad was $5 per ton, then the freight had to be paid to the smelter. After paying the miners, and covering the cost of dynamite and tools, the owner had little money left.

And, unfortunately, the ore occurred in comparatively small pockets and "glory holes" rather than in continuous veins. Found in scattered, irregular bodies, the limestone, dolomite, and chert hills overlooking Rush and Clabber Creeks were already becoming honeycombed with empty tunnels. Finding new ore often proved expensive. The mining business began to slow down.

Then, World War I began in Europe in 1914, and the mines were the center of attention again. Demands for higher quality zinc became urgent as the war escalated, and as the need for zinc increased, the price skyrocketed. It finally went to $160 per ton, which gave mine owners handsome profits.

|

| Miners take a break at the entrance to the Red Cloud Mine, about 1915. |

Now, thousands of workers streamed into the area and at one time there were approximately 5,000 people living in Rush, making it the largest city in Marion County and North Arkansas. Oil engines, huge and noisy, shattered the mountain serenity, while a parade of wagons out of the valley was almost continuous.

Families continued to arrive, determined to adjust to a new way of life as they entered the mining business. Rush had become a swarming, noisy camp town. As new people came in to work the mines, a housing shortage developed. Many of those who came brought tents to live in and these tent homes were scattered over the hills. Some people spoke of Rush as a "Rag Town," a name resented by the old-timers. Still, local folks were glad for the projected growth of the area and were happy for the prosperity.

It became necessary to add a new section of town, and Rush was eventually divided into "New Town" and "Old Town." Besides a school, there was a telephone exchange serving 165 phones, and a bakery where a pie could be purchased for 15 cents. In its heyday, there were two pool halls in New Town, which sprouted up about 1916, three hotels, a hardware store, blacksmith shop, a general store, pharmacy, restaurants, several dwellings, and other business establishments.

There were seven barbers in town, three in front of each of the pool halls. Yet, there was such a demand for haircuts that patrons were required to take a number and sometimes had to wait until the wee hours of the morning to receive their cut. With 18-hour work days, the barbers often partook of spirits to relieve the drudgery of their work. When this happened, it took courage to allow them to proceed with a haircut, and the thought of a shave was out of the question.

Given the need for some kind of recreation during their off-hours in a camp town setting, it seems amazing that order was pretty well maintained in Rush. There were two or three killings reported, but mostly there were rowdy confrontations.

Personality and tempers were not the only difficulties encountered. One definite dilemma which arose because of the large influx of new residents, was the disposal of human waste. With outdoor toilets having to take care of up to 5,000 people the threat of typhoid was always present. While no outbreaks were reported, one spring was condemned because of concerns that the disease had entered it.

Mine accidents were common enough and some were serious. From an account shared by Mrs. Robert Hall (Obeta Hicks) for the "History of Marion County," she told of a mine accident that occurred during her childhood days at Rush. "A large rock fell in a shaft at the Morning Star mine, crushing two men, Logan Setzer and William Jones. I can recall hearing the whistle blow at the Morning Star, signaling a fatal accident had occurred and recall seeing Aunt Lee Ann Setzer, the mother of Logan, coming up the road on her way to the mine to see what had happened. She was crying and praying as she made her way to the scene. Another fatal accident at the Morning Star was when a man fell from the tramway to the ground several hundred feet below."

Sometimes nature itself seemed bent on combat with the residents of Rush. A Mountain Echo edition of May 7, 1915, read: "One of the heaviest downpours of rain in memory of the oldest settlers visited this county Tuesday night of last week... Rush Creek rose rapidly, carrying destruction before the raging wall of water. The residence on the Wilson farm, occupied by Rob Grooms was washed for a distance of about 40 yards, but fortunately lodged against some shrubbery just before it reached the main current of the creek and was stopped, thus saving the lives of the entire family. R. Grooms was not awakened until the rising water had almost reached the bed on which he was sleeping. He hastily carried his wife and two children to the second story of the building where they remained until morning.

"Will Ellrod and Columbus Petty, who were employed at the Morning Star mine were camped between the Chase Hotel and the creek and had their mules hitched to the back end of the wagon and the flood carrried the wagon and the mules before it. The wagon was wrecked, but one of the mules made its way out and was found next morning. The other one, we understand, has not yet been found. The gentlemen were not sleeping in the wagon adn therefore escaped uninjured."

Still the mines and the town continued to flourish. On Nov. 12, 1915, The Mountain Echo showed: "As evidence of the volume of business being done at Buffalo, forty wagons and teams were ferried across the river there one day last week from the Rush and Cow Creek mining Districts. So great has become the business at that place that a shipping clerk has been employed to see after the handling of the ore that is being shipped from that station. It has also become such a stock shipping point that the railroad has recently put in new stock pens for the convenience of the shippers. Verily, the upper White River country is coming into its own."

But by 1917, again because of the high cost involved in locating and extracting the ore, the mining boom began to fade. When the war ended in 1918, it was all over for Rush as a mining town. Prices fell and the camp began to empty out. Early in 1919, the price of ore slumped so badly it was hard to sell at any price, and people began to leave as rapidly as they had arrived. In fact, the desertion of the town was so rapid the druggist was reported to have merely walked off and left his store--which elated the local children, who made the most of the soft drink fountain while it lasted!

Attempts to revive the area were made in the 1920s, but met with failure due to the lower cost of imported zinc. Hopes for another boom rose in 1958, when the Rush Creek Mining Company was organized and built a new mill not far from the banks of the Buffalo. It was hoped that zinc would become a big factor in rocket building, but the mill did not rejuvenate the old mining camp. Rush was now known as the lost corner of the Buffalo watershed.

For a time the abandoned Rush mines were a haven for collectors--"rockhounds" who explored the abandoned mines in search of bits of ore and pink dolomite and calcite crystals. The carbonate ore, with its glossy or pearly luster, was often called "turkey fat" by the miners, and was particularly interesting to collectors. They would find the tunnel entrances by looking for their "spoil banks," which are described as anthill-like piles and spills of waste rock. Eventually, the tunnels began caving in and it was necessary to close the mines to trespassers.

The area is now maintained by the National Park Service, where wayside exhibits point out key sites of the Historic District. Activity is limited to those passing through on their way to the river, or when tourists stop to gaze with curiosity at the remains of the once thriving town.

Yet, in the springtime, a colorful assortment of flowers lines the roadway. While some are wildflowers, it is obvious that many varieties were planted by loving hands long ago. They are the living remnants of the town--the legacy passed on by those who sought to bring a touch of softness and beauty into their world.

|